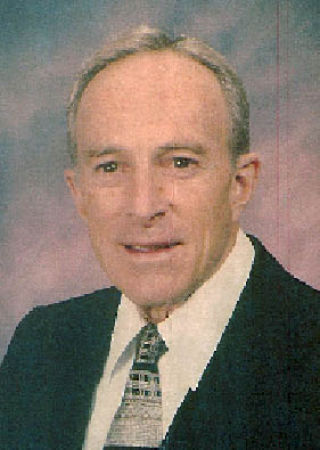

ARLINGTON — If a man’s friends are a measure of his life, then Dr. Norman Zook lived a very full life indeed.

Hundreds of friends, family members, colleagues and former patients gathered at the Arlington Free Methodist Church Sept. 3 to pay tribute to Zook, who passed away Aug. 26 at the age of 81.

Zook was honored for his service in the Air Force during World War II, when he oversaw prisoner care in Okinawa in 1945, and for the following decades of medical care that he provided to others.

Zook met and married his wife Laurine while attending Seattle Pacific College, and after medical school at the University of Oregon, his family, which had grown to include daughters Tamara and Debora, moved to Arlington in 1956.

Dr. Ben Burgoyne had met Zook years before, and took pride in telling the other attendees of the Sept. 3 memorial services that he’d persuaded Zook to come to Arlington.

“I knew he’d be a wonderful partner and that I could trust him to come,” Burgoyne said of his former medical practice partner. “I couldn’t have had a better partner in the world.”

Zook remained a practicing doctor in Arlington for the next 35 years, before his retirement at the end of 1991, with Laurine giving birth to daughter Tonya and son Norman along the way. Burgoyne’s wife Bonnie recalled the Zooks being welcomed into their own family, with their respective children treating each other like cousins.

For someone who was retired, Zook seemed to have trouble sitting still, since he continued to fill in for other doctors and even travel overseas as a missionary. He left his practice twice in the 1970s, for stints of two years each, to serve as a missionary doctor in South Africa, and his later years of missionary service saw him and Laurine serving in Burundi during the 1993 coup.

Zook was lauded by many memorial service attendees as a man of faith, not only in his medical trips to Haiti, the Dominican and Central and South America, but also in his service to the Free Methodist Church. Linda Dennis credited Zook with restoring the Christian faith of herself and her husband.

All of Zook’s children recalled their summers spent sailing the San Juan and Gulf islands with their father. Son Norman took pride in the heritage and positive examples that his father had given him, while daughter Tammy admitted at she and her father fought occasionally, but celebrated the fact that, even that the end of his life, he was able to give and receive love. Tammy’s sister Debbie elicited laughter when she admitted “people tell me I look just like my dad,” and again when, because she’d forgotten her glasses, she asked her brother to read “Why a Daughter Needs a Dad.”

Zook’s nephew, Donald Anderson, read aloud the memories of Zook’s sisters, Nellie Fenwick and Georgia Anderson, who were unable to attend. They recalled catching pollywogs and delivering milk with him as children, and receiving support for their own ministry work from him as adults. Their accounts of his childhood interest in medical dissection earned more laughter from the crowd, who nodded their heads at their fondness for his “Reader’s Digest jokes and hearty laugh.”

Daughter Tonya alternated between laughter and tears as she offered her own account of her father, remembering his tears at his grandmother’s funeral, and on her 16th birthday. She noted that her dad’s profession gave her a first-hand look at some life-lessons, since she watched while he delivered babies and treated the wounds of those who had driven under the influence.

During one moonlit, snowy walk in the country, a shooting star sparked a discussion of faith between Tonya and her father.

“Dad seized the opportunity to talk about God’s marvelous beauty in nature, his wonderful design in the universe, his love for mankind and his attention to detail in creating me,” Tonya Sanders said. “I was someone who was very much loved by my creator and my earthly father. This may well be my favorite memory of my dad.”

The speakers tempered their grief by observing, as Zook’s sisters did, that “it won’t be long ‘til we’ll be joining you.”