LAKEWOOD – Daniel and Lisa were in a tent in a homeless encampment early Thursday afternoon.

Marysville Police Officer Mike Buell and Arlington Officer Ken Thomas approached the tent and asked if they wanted to talk.

Despite the uneasiness in his voice, Daniel did. The officers explained they are part of a new program in North Snohomish County that wants to help the homeless.

With the officers were two newly hired social workers – Rochelle Long for Marysville and Britney Sutton for Arlington. They talked to Lisa mostly about the opportunities available to help them get off drugs, including detox, treatment and temporary housing.

While the couple did not go with them, Thomas was confident they eventually would. The alternative is incarceration.

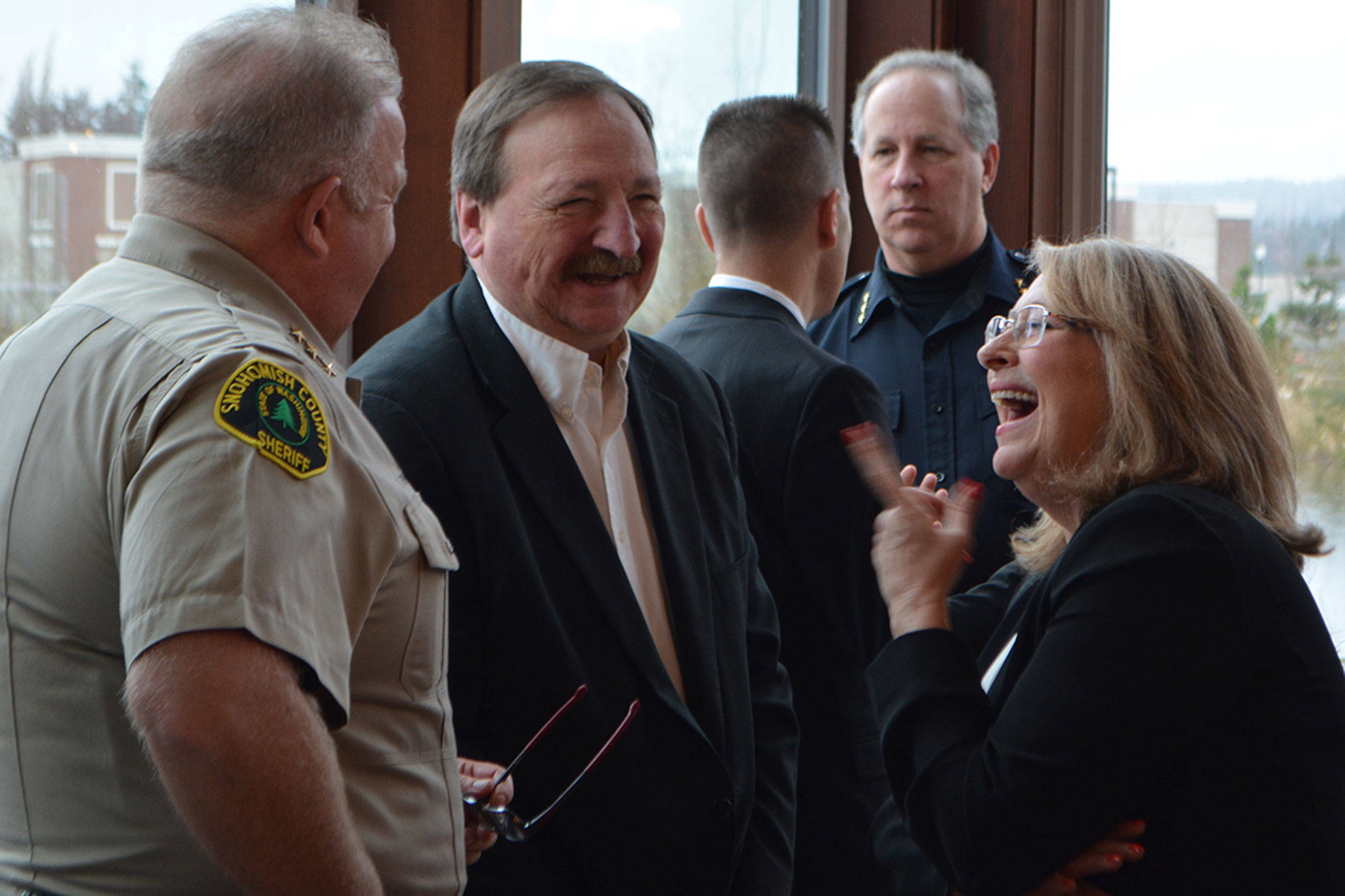

The tour of the homeless camp came after a meeting of city and county officials nearby at The Lodge housing development.

Officials announced new tools to help address homelessness locally through the launch of a new North County Office of Neighborhoods Unit, and a new law that cracks down on chronic nuisance properties.

Snohomish County, and the north county in particular, is taking a unique and innovative approach to tackling the opioid epidemic that stresses help for the homeless and drug-addicted willing to change, and enforcement if all else fails, County Councilman Nate Nehring said.

“We will absolutely work with you and for you to get you the services that you need, whether it’s housing, treatment, job training, whatever it is,” he said. “But we will absolutely not tolerate, and will not enable, a lifestyle of heroin and opioid abuse, of committing property crimes, and of destroying neighborhoods in our communities.

Arlington Mayor Barb Tolbert and Police Chief Jonathan Ventura said the embedded social worker approach offers a viable and compassionate solution to dealing with homelessness and real help for those who want it.

Tolbert said the governments working together, especially in the Smokey Point area, offers a path forward for troubled individuals instead of shuffling them from one jurisdiction to another.

“I’m very pleased that we no longer have that ‘hamster wheel’ of sending people around, but actually are going and finding where they’re at, and offering them a true path to a different style of life,” she said.

Tolbert is already looking ahead at how to keep individuals focused on improving their lives after treatment, though housing support and job training.

“This is the beginning of great change in our community,” she said.

Ventura said law enforcement has been used as a hammer, traditionally.

“And as you know, if you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” he said. “It’s time to change that paradigm.”

Ventura introduced Officer Ken Thomas as Arlington’s lead in the embedded social worker program. The 20-year police veteran worked in the schools, as a detective, and has a master’s degree in Criminal Justice.

When he asked Thomas why he was interested in the program, the officer said “he was interested in seeing something different that hadn’t been seen in law enforcement before, and leaving a legacy in a positive way.”

He also introduced social worker Britney Sutton, who started on Monday, and will be working with Thomas.

Thomas got a head start three months ago, gaining contacts, going out to the camps and establishing a rapport with some of the people in need of services, and he connected with the Sheriff’s Office and team working the south county.

“In the short time that he’s been doing this, Ken has bbeen able to get 5 people into treatment, a dozen people in assessments, and he he has a dozen more lined up to get assessments in line for treatment,” Ventura said.

This is the way of the future, he said. “We believe that there should be accountability. We know what doesn’t work, so it’s time that we try something else.”

Sheriff Ty Trenery said in his early policing days, he believed the only way to really solve problems was a “pair of handcuffs and a trip to jail.”

After becoming sheriff, he said, “I quickly learned that this opioid crisis and our homelessness crisis was much more complex, and that the traditional methods of policing, quite frankly, didn’t solve the problem.”

He started noticing that 30 percent, of about 40 people, of the jail population each day were heroin addicts. He found out 53 people had been arrested over 30 times and 80 percent of them were addicts. Instead of that, how about “getting them off the streets and into healthy lifestyles?” he asked.

Trenery said a major problem now is not enough services locally. Most who want help have to be sent out of this area. So, the county is working on a 44-bed diversion center, remaking the Carnegie building and revamping Denney Juvenile Justice Center. The sheriff said law enforcement isn’t getting soft. “This isn’t a hug-a-thon,” he said.

Nate Nehring authored a law that just went into effect Wednesday that makes it easier for the county to crack down on nuisance properties. The police and social worker teams will also go to those sites to help those with addiction issues there.

“This new ordinance will give law enforcement better tools to more effecitvely and efficiently address the nuisance homes and encampments that are bringing crime and drugs into Snohomish County neighborhoods,” Trenery said. “We need to hold drug dealers accountable, and we need to find drug treatment for addicts.”