ARLINGTON – On a recent patrol, officer Ken Thomas arranged a meal with a homeless man to get him into treatment, drove another man to a detox center, and stopped by the new Snohomish County Diversion Center to check on a client – all before lunchtime.

Thomas is teamed with embedded social worker Britney Sutton. They form Arlington Police’s community outreach program.

Their mission is to assist the homeless with alcohol or drug addition – mainly opioids – and untreated mental illness to get them the help they need, off the streets in Arlington and Smokey Point, and back on their feet again.

Arlington’s team is also part of the sheriff’s North County Office of Neighborhoods Unit, which includes a Marysville contingent that is sending human services and law enforcement teams into encampments to connect with vulnerable populations, while reducing the likelihood of re-offending or incarceration.

Launched six months ago, word has spread through camp life and among drug users that if you’re looking to get clean and sober, there is no time like the present.

“When people really want help, we can make things happen quickly,” Thomas said. “As an officer on the street, you kind of go: ‘Well if you go over here they can help you,’ but now I say, ‘I can take you there. Let’s go now.’”

While they’re still running into some who are resistant to getting help, “with the cold weather coming, that might push them over the edge when there will be a little more desperation out there in the encampments,” Thomas said.

Thomas and Sutton are well-connected and savvy navigators of the human services maze. They can help clients obtain identification, health insurance and Medicaid benefits in a flash, arrange chemical dependency assessments, detoxification, inpatient and outpatient services and housing, and a ride to get them there.

“The ability to physically give hands-on help for someone living in a tent to get resources makes all the difference,” said Sutton, who worked previously as a psychotherapist for Compass Health. “We’re continuing to make really great connections outside of human services and police,” said Sutton, citing Catholic Community Services and the Stillaguamish Tribe’s methadone treatment and healing center for assessments.

The Arlington Community Resource Center has emerged as a major hub of services that the embedded social worker program relies on. The center has helped the Stillaguamish Valley community rebuild after the Oso slide four years ago. T that will continue, but they are embracing their new challenge to help the homeless with everything from housing to food and clothing. Sutton talked about a mother and her kids who were about to lose their space in a local shelter. Sutton connected them with housing navigator Lori Morgan, who was able to extend their shelter stay two weeks, while she secured housing for them.

“Without Lori, they would have been kicked out,” said Sutton, who got heartfelt thanks and hugs from the mother.

Another client cold-called to say he had been trying for months to get medical coverage. Sutton met him in the DSHS parking lot in Smokey Point, and she was able to get him coverage while he stood by. “He was awestruck.”

Building trust

When you’ve been in law enforcement for over 20 years like Thomas has, there isn’t much that surprises him. However, there is one unexpected facet that does. “I’m surprised by the way that homeless people trust us,” Thomas said. “It’s not so much a surprise, but it’s interesting that it wasn’t that hard to build the trust. Some of the people have mental health issues, while they and others have had lots of let-downs in their lives.”

Tramping into the woods to visit homeless camps isn’t the only way the team reaches potential clients. Sutton said they distribute flyers and business cards in camps and in public places, talk to clients who aren’t ready to get help but know someone who might be, and receive referrals for contact from fellow officers and team agencies. On the recent morning patrol, Arlington officers passed on a request for Thomas to meet a homeless man who was apparently living out of his pickup. Thomas pulled into a parking lot between the Denny’s and Arlington Motor Inn at Island Crossing near Interstate 5.

While talking with the man, he learned that he had been homeless for months traveling between Arlington and King County, and was using drugs, with hints there might be a mental health issue to evaluate, too. He handed the man a flyer with contact information for social health services and community resources, and arranged to meet him the next day for a meal.

“He’s stuck here circling around trying to figure out what to do here,” Thomas said. “He’s using our resources though. He knows about the resource center, so that’s good. We always push them in that direction to get started.”

Others aren’t ready to turn the corner so quickly.

“Some clients aren’t ready to go full bore, and that’s OK,” Sutton said. “We say, ‘get prepared, and maybe get just this or that little piece done.’”

Thomas said that was the case for Phil, a homeless drinker who got caught in the first rainy deluge this fall, got admitted into Cascade Valley Hospital ill with his clothes still soaked, and wanting to get off the streets. “A day later, we had him in a hotel room, and things moved right along,” Thomas said.

The next morning, Thomas pulled into the Travel Lodge in Everett to pick up Phil, a genial man in his late 50s who was feeling better after a night spent watching Living Alaska on HGTV, a cold climate he has no desire to visit. He still bemoaned the nagging bump under his foot that sent shots of pain up his back when he stood, but he welcomed the donated new jeans, wool socks and work boots. “I’m glad for all the help I’m getting, and I really do want to get cleaned up,” Phil said during a smoking break in the parking lot. A backpack and walking stick his only possessions as he went for a ride to the Evergreen Detox Facility in Lynnwood, where he spent five days.

Thomas said, “When he’s clean, they’ll bring him to the diversion center. He’ll be able to stay there until he’s ready to get his life together.” He said to Phil: “Britney will check in on you. You couldn’t have picked a better social worker.”

The diversion center, which opened in June, didn’t exist the last times Phil sought help.

Thomas said before the center was an option, he saw many occasions where an addict would be back on the street after treatment or detox because case workers were unable to find a bed to help them with the next stage of sobriety.

Diversion Center

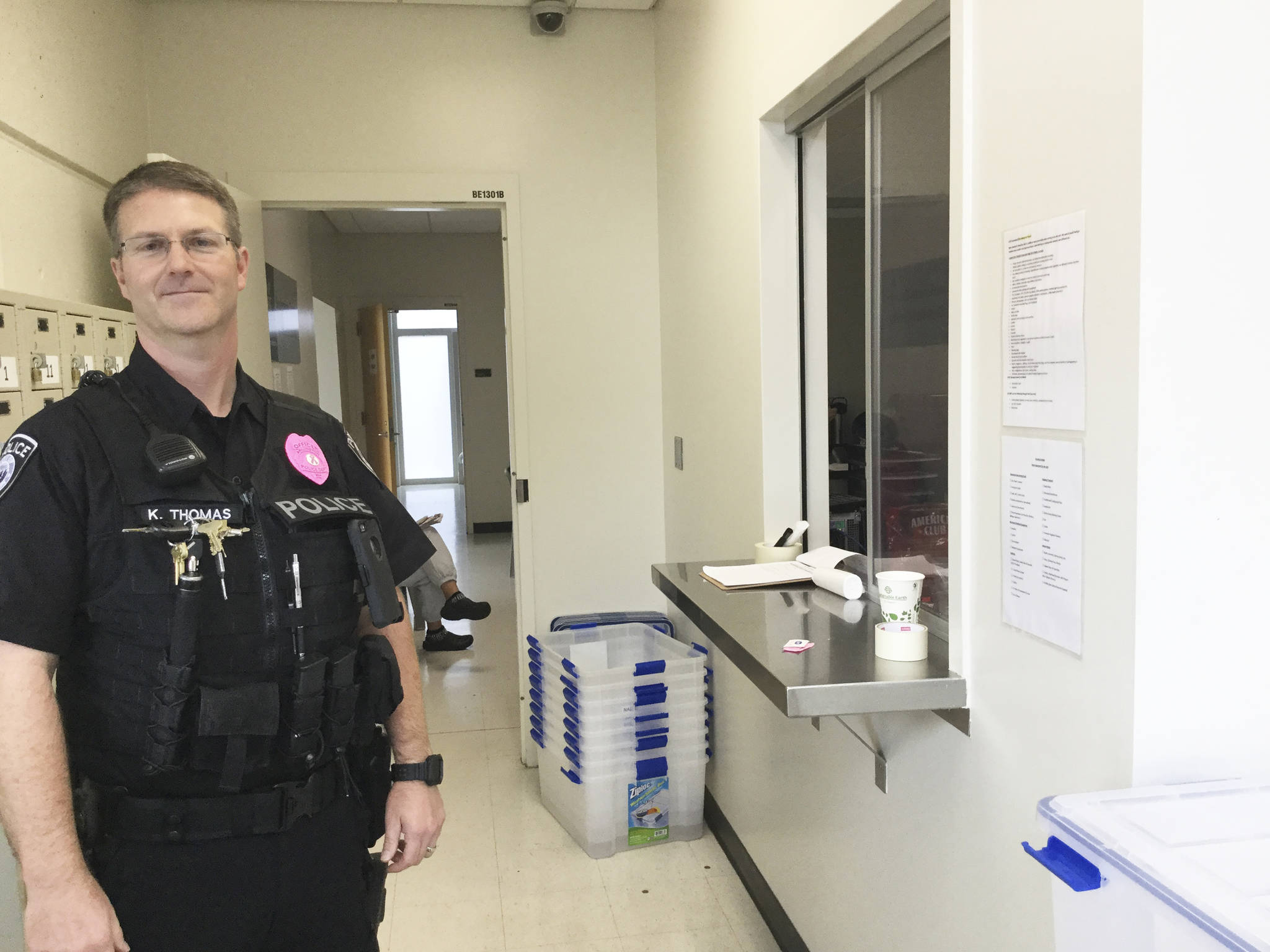

On the return from Lynnwood to check on Zach, a client with a drug addiction seeking housing during detox, Thomas stopped by the 44-bed diversion center at 1918 Wall St., the former work release center north of the county jail. Prior to the center opening, there were only 32 detox beds around the county.

Thomas said driving clients to the center has caused more than one to say, “Woah, I’m going to jail?”

The center, with floors and sleeping quarters divided by gender, is a residential, short-term place for individuals to begin breaking out of the cycle of addiction, seek medical attention and take care of other personal needs that get cast aside when drugs take over. In some cases, two-week stays can extend to 30 days depending on the situation.

It can also provide immediate access to short-term detox and treatment for addicts on the street as well as long-term treatment, housing and job opportunities. The center has two case workers and EMT services 24/7. After checking in, residents are given sweats to wear while their clothes are washed and dried. They’re permitted to keep personal items not on a posted list, and they’re issued a bed and their own private locker. The center includes lounging aress to watch TV and relax, and vending machines.

Pioneer Human Services is operating the center, a one-year, $1 million pilot project that could become a model for other communities statewide.

Because of that potential, a lot of data is being collected, which will be provided to the state Commerce Department and lawmakers. Looking at the bigger picture, Thomas said the number of camps has gone down in his jurisdiction, based on his visits into the woods. So has the number of drifters and vagrants in the Smokey Point area, he added, based on observations and conversations with business owners.

The decline is a reflection of a combination of things: homeless people leaving, some others weary of constant questioning by authorities, and Marysville police’s emphasis on trespassing enforcement on properties where encampments have popped up.

Arlington Police Chief Jonathan Ventura said earlier this year that law enforcement has been used as a hammer, traditionally, where everything looks like a nail. While enforcement has its place, he favors a more constructive approach.

“We believe that there should be accountability, but we’ll bend over backwards to give people the opportunity help themselves,” Ventura said. “We know what doesn’t work.”

Follow up

• The homeless man living in his truck contacted at Island Crossing did not follow through on meeting with Thomas the next day, but the officer is still trying to connect with him.

• Phil is staying in the diversion center now after five days in a Lynnwood detox facility after an alcohol assessment.

• Zach is no longer at the center; the ESW team and housing navigator found a place for him.

By the numbers

• Since the center opened June 4 and through Sept. 25, 201 clients came through the door, with 23 on average occupying beds in the 44-bed facility.

• 79 clients have entered treatment, 61 walked away from the program, housing was secured for 17 individuals, and 10 others were discharged for behavioral reasons. The average stay has been about two weeks, with 60 days the maximum staying time.

• The Sheriff’s Office accounted for almost half of client referrals to the diversion center, while Arlington referred 35 individuals, Marysville and Monroe 28 each, Everett 15 and Lynnwood 4.