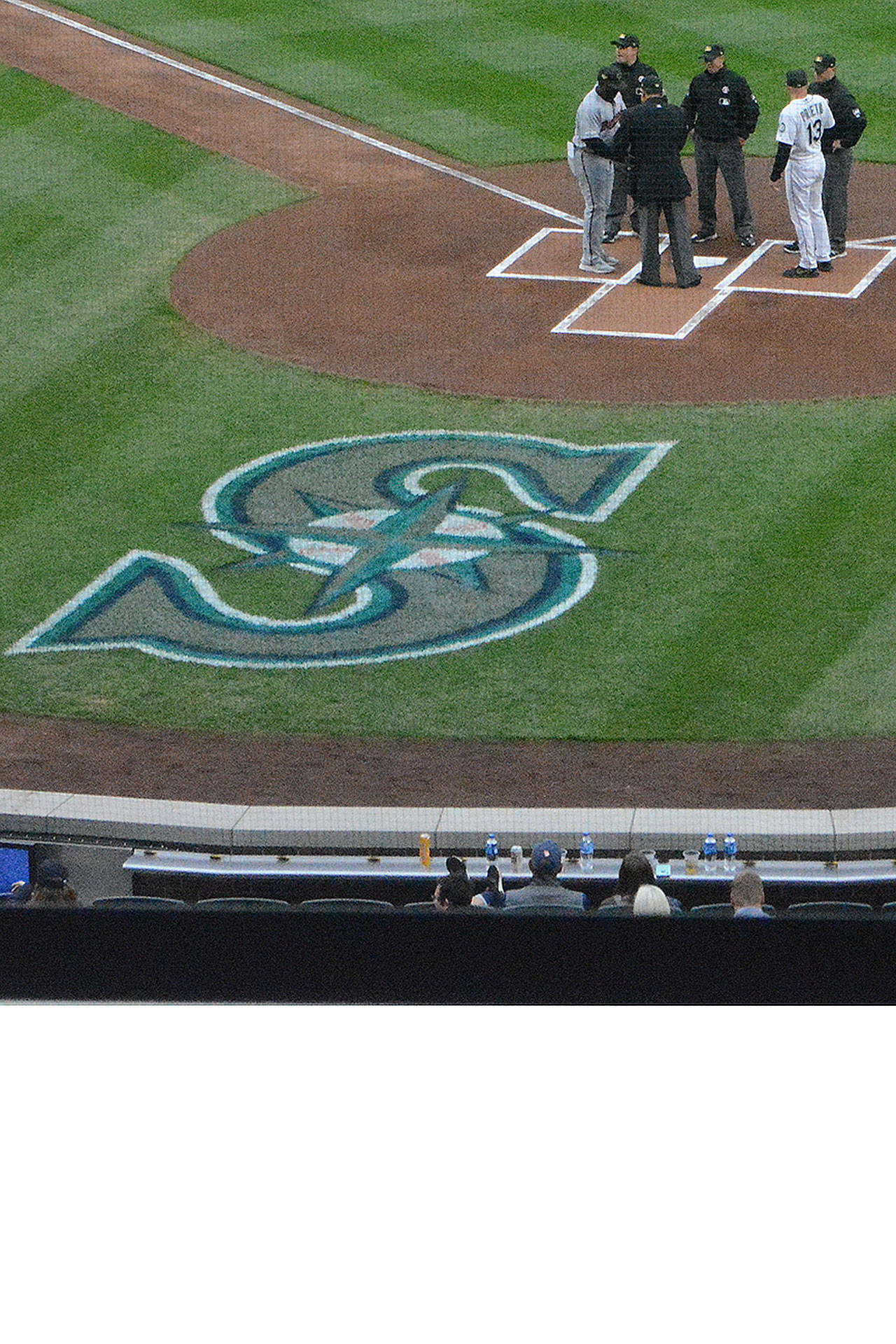

MARYSVILLE – Tripp Gibson of Marysville started at second base in a recent game between the Twins and the Mariners – as the umpire.

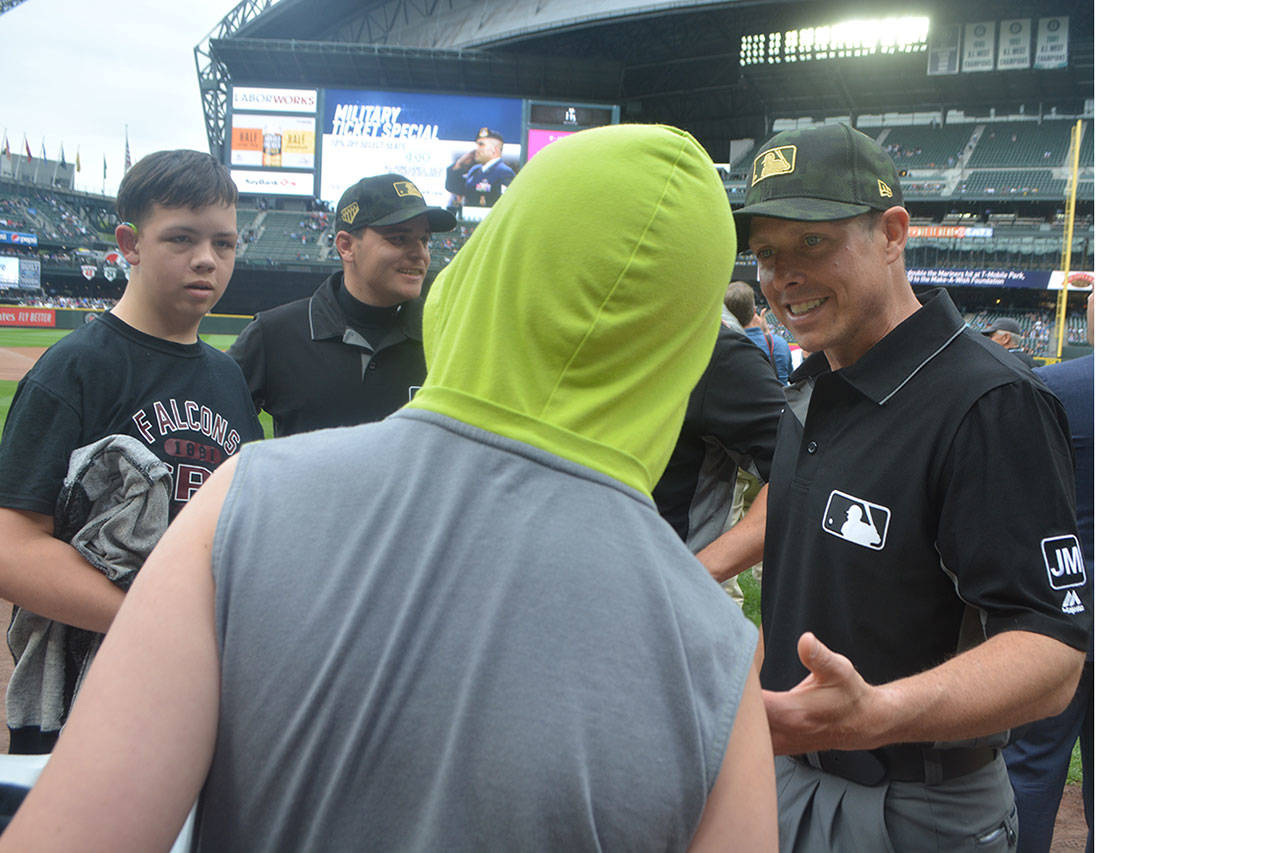

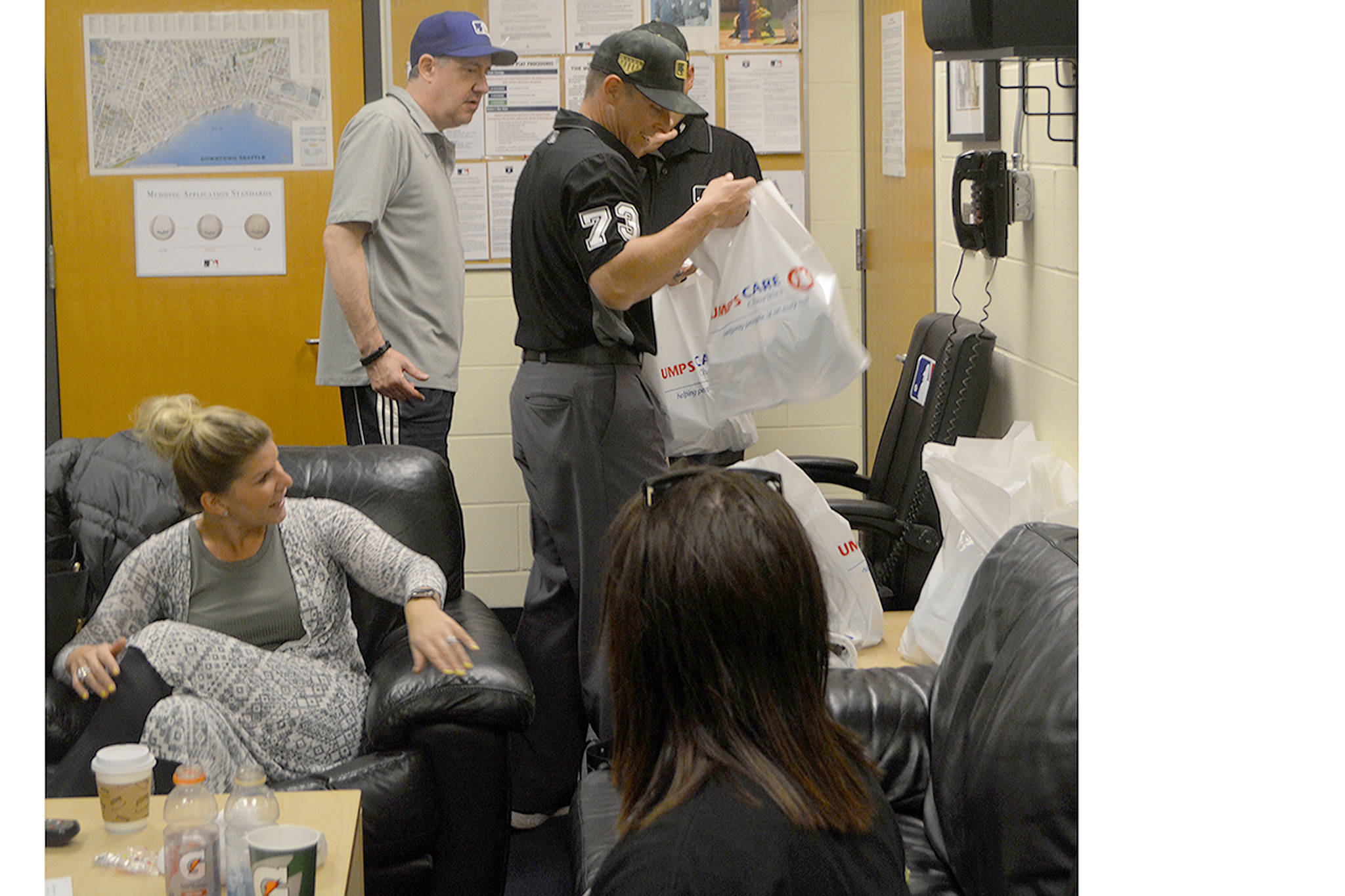

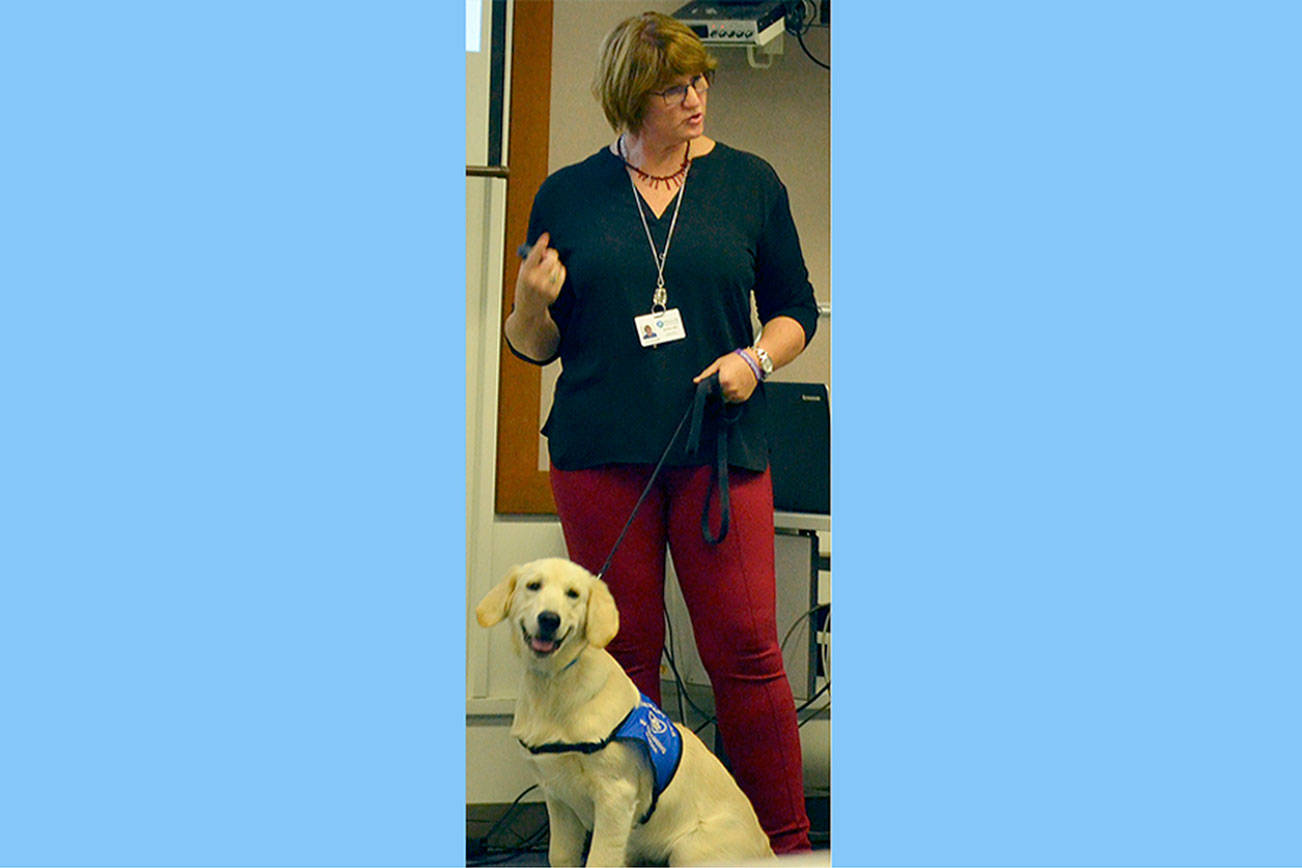

It was one of the rare times during the season that he got to see his family. They and friends visited with him in the ump’s locker room before the game. As part of charity work he does with UmpsCare he met with two teen-age boys who are hoping to be adopted. With his ever-present smile, he gave them bags of goodies, along with the thrill of going out on the field. “They do not get a lot of fun experiences,” said his wife, Danna, a graduate of Marysville-Pilchuck High School.

Her mom, Anna Tate, also of Marysville, is proud of her son-in-law. “He’s a doll – a true Southern Gentleman,” she said.

As the game started Gibson jogged around first base and headed to second, doing stretches once there. Good thing because when the game started he was jogging all over the place getting into position to call plays. He moves from one side of the base to the other, depending on whether it’s a left- or right-handed batter. He spends a lot of time trying to get out of players’ way as they get in position to make plays. On an extremely close play at second he was right on top of the bag, but the call was easy as the infielder dropped the ball.

Growing up

Gibson, 37, grew up in a small town in Kentucky. He got the nickname “Tripp” as in triple from his family because he was the third Hal after his dad and grandpa.

He started playing baseball at a young age, scoring the winning run in the 13-year-old World Series in Nebraska. He played varsity baseball for four years on a team that was usually ranked in the Top 10 statewide. He was recruited to play in college, but was burned out, so he decided to focus on his education at Murray State University. He wanted to teach high school art and history, along with coaching baseball.

But his focus changed that summer.

“I went down to the local Little League fields and was immediately baptized by fire,” he said. “They threw me behind home plate. I kinda just felt this connection and passion that I did not have in any other job.” He worked as many games as he could. He made enough money to move out of his parents’ house and into the fraternity Pi Kappa Alpha.

“It was the best decision I ever made. It taught me so much about time management but also what it takes to try to be the best at something in a larger-picture-type way,” he said.

He umpired more and more games. “There was no distance too great if the money was right,” he said.

Other umps became friends. “We had fun after the games talking rules and studying up on the mechanics of what it took to get better,” he said. He recalls umpiring as many as five games in one day then going to the local laundromat, studying and talking “shop” with the other umps.

He started working high school games and attending camps. Then it was junior college, NAIA and Division 3 ball. When he made it to the Independent Professional League he decided he needed to attend a professional umpire school.

Which is what he did after graduating after 5 1/2 years from Murray State. In 2006 he went to the Harry Wendelstedt School for Professional Umpires in Daytona Beach, Fla. It was five weeks long, 10 hours a day, six days a week. “You spend the mornings in the classroom where you break down the entire Official Rules of Baseball Rulebook. It’s the most unorganized book ever assembled,” he said, adding it’s much better now. They worked in the field afternoons. “You work drills, drills and more drills.” The last two weeks they work live games.

He finished second in his class of 175, qualifying him for a more-advanced camp called the Professional Baseball Umpire Corps.

After that he was hired as a professional umpire and was assigned to the New York-Penn League, equivalent to the Class A Everett Aquasox, he said.

He spent the next nine years in the minors traveling all over the country in cars, vans, etc. In 2011 he was promoted to AAA Pacific Coast League. He worked Major League spring training in 2012, but it wasn’t until Jan. 9, 2015 that he made it to the Big Leagues full-time.

Highlights so far including umpiring Wild Card games at Yankee Stadium in 2017 and Wrigley Field in 2018.

Another highlight was umpiring in Japan during Ichiro’s last games. Danna went, too.

“I never thought I’d want to go, but it was unbelievable,” she said. “The fans just loved Ichiro so much. And I was proud of my husband at the same time.”

Move to Marysville

Gibson came to live in Marysville because of Danna. They met in 2010 while he was working the Arizona Instructional League. They have been married seven years and have two sons, ages 6 and 2.

Danna said many of the umpires live where their wives grew up because of the support system.

“I’m lucky to have my parents in town and a network of friends,” Danna said.

He does get about five months at home in the offseason, when they do as much together as they can. They live on Lake Goodwin and like to go fishing. They attend The Grove Church and participate in city parks activities.

They also see each other the one to three times a year he works in Seattle. And a few times a year they will fly to see him, usually somewhere on the West Coast.

“And we FaceTime as much as possible,” Gibson said. “Being gone is so stinking hard. They have adapted, but we just do the best we can.”

Danna added, “He’s so present even though he’s so far away.”

She said she recently quit her job so she could stay at home and provide a more-stable environment for the kids.

“It’s not as glamorous as it might sound,” she said of the life of a Major League umpire. “The career is a lonely one. He lived like a nomad for ten years.”

Danna said he spend 250 days a year in hotels. They have to book their own hotels and flights. She added in the Minor Leagues they don’t make much money.

But according to MLB.com, Major League umpires get around $120,000 to start, and senior umps can earn $300,000 a year. Gibson said he would recommend it as a career.

“You have to be able to adapt to change, listen, take constructive criticism and be able to grow in your profession.”

His favorite part of the job is being behind the plate, calling balls and strikes. He admits it’s a hard job.

“We miss calls. We don’t want to miss a call. But it’s human error,” he said, adding they usually don’t even know when they’ve made a mistake until later when they see it on video.

As for complaining fans, Gibson said it’s not like umpiring at lower levels where they are right in your face. “It’s a buzz,” he said. But the time has gone fast, Gibson said.

“It’s crazy. It seems like yesterday I was working on dirt infields in August in Kentucky getting yelled at by 14-year-olds’ moms or getting an escort by the AD at some high school mad about a call I had made,” he said.

—————————-

Charity event

MARYSVILLE – Danna and Tripp Gibson both are community minded.

Danna is involved in the Marysville School Foundation, raising money for high school scholarships. “My heart is community,” she said.

And she also helps her husband at UmpCare’s 5th Annual All-Star Break Golf Scramble July 9 at Cedarcrest Golf Course. The motto of the nonprofit charity is, “Helping People is an Easy Call.”

The four-person best-ball tourney starts at 8:30 a.m. Cost is $150 a person. Contact Jennifer Jopling at 801-599-1706 or jennifer.jopling@UmpsCare.com.

Gibson used to come home and play golf with his buddies during the all-star break, but then it turned into a tournament. The 144 spots always sell out.

Fellow Major League umpires from Washington Quinn Wolcott and Mike Muchlinski, along with an NFL ref from Seattle, an NHL ref in Lake Stevens and NBA officials, all help out.

“The camaraderie between the sports… It’s really cool how they support each other,” Danna said. She said the golf tourney gets lots of support from community leaders and businesses. Mayor Jon Nehring even plays.

“It’s great for Marysville,” she said, adding there are prizes, a silent auction and a raffle.

Proceeds go for the on-the-field experiences for underserved youth, to help kids who are terminally ill at Seattle Children’s Hospital through a build-a-bear project, and for scholarships for kids adopted later in life who have not had a chance to build up a college fund.

“They are so humble,” she said of those kids. “They have so much to give considering how much they’ve been given.”