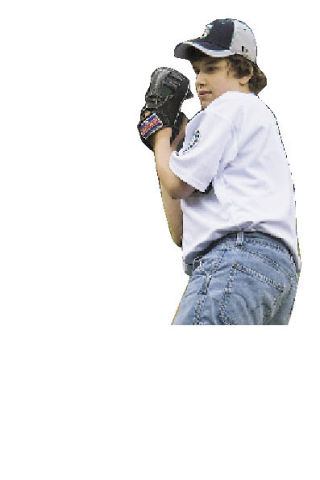

SEATTLE — Arlington’s James Wilson literally stood out from the crowd in Safeco Field, May 7, but his parents say he’s just like any other 14-year-old boy.

James has autism, and he was chosen to throw out the first pitch at the second annual Seattle Mariners’ Autism Awareness Night, after parents Jay and Carrie both entered an essay contest through Autism Speaks.

“We’d gone to the first home game of the season when we saw an Autism Speaks booth,” said Jay, who goes to a lot of games with his son. Through the booth staff, Jay found out about the Mariners’ Autism Awareness Night fundraiser for Autism Speaks. Both Jay and Carrie submitted essays about James, but Jay’s essay won James his shot on the pitcher’s mound.

“You always have great expectations for your kids,” Jay said. When James was born, Jay noticed his son’s large hands. He wrote in his essay, “The first thought that went through my mind was, ‘With hands like those, put a baseball bat in them and watch this kid hit the ball a mile!’”

James was five years old when he was diagnosed with autism, and Jay was told that his dreams of his son becoming “a baseball star” would never come to pass.

“God had other things in mind for him,” Jay said. He and Carrie spent the years that followed learning all they could about autism. He wrote in his essay, “We now had new goals for our child, and ourselves. We would work hard as parents to help our child become a highly functioning member of society and live a normal life, just like everyone else.”

James’ parents were told that he would probably never be able to swim, ride a bike, look people in the eye or even swing upside down on a swing set. Jay and Carrie both worked hard with their son to prove all these predictions wrong.

“James has become such a good swimmer that I don’t even worry when he swims to the bottom of the Marysville-Pilchuck High School pool, even though it’s 10 feet deep,” Jay wrote in his essay.

As James’ coordination improved, his father decided to train him in team sports skills, from basketball to baseball. Although James couldn’t grasp the concept of team sports, he enjoyed the company of children his own age.

“At that point, I realized that James was really never going to be that major leaguer that I had always dreamed about,” Jay wrote. “But that did not matter much to me anymore. It was satisfaction enough to watch him achieve the little things.”

One of James’ achievements is becoming his father’s “baseball buddy” at the games. While James was initially wary of the large crowds and loud noises of the stadiums, he soon grew to enjoy watching the games, first with the Everett Aquasox, then with the Mariners. He began by bonding with the Frog and the Moose, the teams’ respective mascots, then learned that he could eat pizza, popcorn, cotton candy and snow-cones, “all of his favorite foods,” at the games.

Now, James is a middle school student who runs the 100-yard dash and throws shot put for the track team. Carrie added that her son has even picked up a few other traits of an average teenager.

“He tried to get away with skipping class recently,” Carrie said. “I was almost proud, because it was such a typical kid thing to do, but at the same time, we made sure he knew that it had consequences and that he won’t be doing it again.”

While both father and son were interviewed by FOX Sports, Jay was much more moved by another conversation he had on the field.

“I met the judge of the essay contest,” Jay said. “He shook my hand and told me I was an inspiration. He has a six-year-old son, so he’s going through what I went through and it gives him hope that he’ll be able to take his son to Mariner games one day.”